I'm taking a quick break from the world of never-ending subsidies with this post. Just over a week ago, Elizabeth Warren was inaugurated as the first female Senator from Massachusetts. One of the thirteen original colonies, Massachusetts has been selecting Senators since 1789, a mere 224 years ago.[fn]Senators were selected by Legislatures rather than voters for a good part of this time, but even they could have selected a female. The fact that women couldn't vote clearly made such an outcome less likely, though[/fn] It took more than 75 Senatorial terms before this ostensibly liberal bastion elected its first woman. The State was ahead of many others in the country when it allowed the first blacks to serve as jurors back in 1860. Women, on the other hand, could not be on juries until 1950. We've yet to elect a female governor either, though Jane Swift served as Acting Governor when her boss (following the pattern set by his boss before him) left the job mid-term for greener pastures.

Although the State has fine institutions of higher education for women dating back almost 200 years (Wheaton and Mt. Holyoke were chartered in the 1830s; Radcliffe, Smith, and Wellesley in the 1870s; Simmons in 1899), the role of women in political life has been marginal. The ability for Elizabeth Warren to win a position in the Senate is part of a much longer set of smaller-scale victories by women going back generations.

One of those women was my grandmother, Freyda Koplow. She was elected to the Massachusetts House of Representatives in 1955. The directory of public officials that year shows only three female Representatives (of 237 listed) and three female Senators (of 40 listed). Eight years later the figure was similar, with five females in the House and two in the Senate. The majority of the women (including my grandmother) affiliated with the Republican party. She served in the House until her appointment by Governor John Volpe in 1967 as the State's first female banking commissioner, a position she held until 1975. The initial salary: $15,000 per year.

She channeled NJ Mayor Cory Booker eighty years ago, when, in 1931, she and a classmate tested if they could live on the old age pension (at the time of $6.25/week) as part of their Masters' thesis at Simmons. This is equal to about $13/day in today's dollars, a good deal higher than Booker's $4.32 food budget, though in fairness, their budget had to cover a wider range of expenses than just food.

Reading press articles about her from the time can be entertaining. Most reporters couldn't fully escape asking at least some inane questions (her favorite china pattern, for example) rather than just talking about the job. Even this generally job-focused article from Business Week in 1967 on the "Nation's only lady banking commissioner" couldn't resist at least a little kitchen talk.

Growing up, I did have a vague notion that what she did was not typical for her gender. I do remember visiting her office a couple of times, as well as attending her swearing in for her second term as Banking Commissioner. In truth, though, my most vivid memories of visiting her at work are not of the gender mix of the office and how she was forging new paths. Rather, it is of being a little kid on an elevator full of smokers, and trying to keep breathing long enough to reach her floor.

Growing up, I did have a vague notion that what she did was not typical for her gender. I do remember visiting her office a couple of times, as well as attending her swearing in for her second term as Banking Commissioner. In truth, though, my most vivid memories of visiting her at work are not of the gender mix of the office and how she was forging new paths. Rather, it is of being a little kid on an elevator full of smokers, and trying to keep breathing long enough to reach her floor.

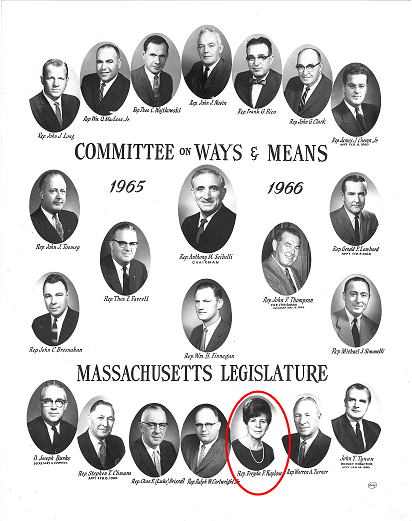

The Committee on Ways & Means class photo (high-res version here) for the 1965-66 session brings far more clarity to how atypical it was to be a woman in public office in those days.

There are so many questions I wish I'd asked her about what it was really like to be among the only female in these long-established institutions. The bits I've heard from others over the years tell me that the barriers she broke did give at least a few other women the confidence to run for election and enter these public institutions themselves -- just as I'm sure some of the women that preceded my grandmother to the State House served as role models to her. Even in Massachusetts, women are serving more frequently and at higher levels of all sorts of institutions and organizations. Elizabeth Warren marks a big step up in this long evolution, and her success will no doubt help it continue well into the future.