coal subsidies

Coal and Renewables in Central Appalachia: The Impact of Coal on the West Virginia State Budget

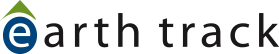

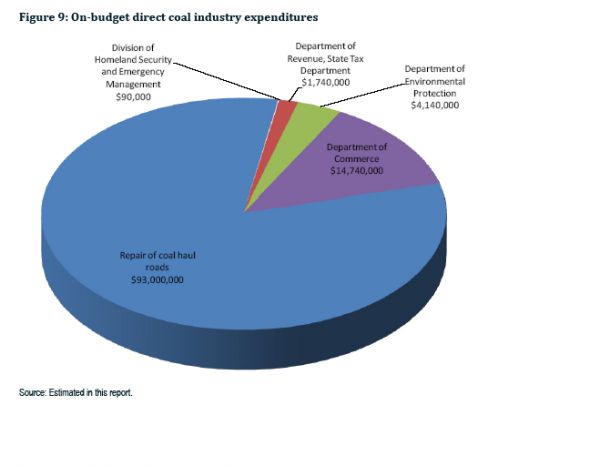

In this report, we examine the net impact of the coal industry on the West Virginia state budget by compiling data on and estimating both the tax revenues and the expenditures attributable to the industry for Fiscal Year 2009: July 1, 2008 through June 30, 2009. In calculating these estimates, there is an inherent degree of uncertainty associated with the results. We do not claim that our accounting of revenues and expenditures is precise; in fact, we round our estimates so as not to provide a false impression of precision.

Coal and Renewables in Central Appalachia: The Impact of Coal on the Tennessee State Budget

Although coal has played an important historical role, the Tennessee coal industry now provides few jobs to state residents, and does not provide significant revenues to the state budget. In fact, as estimated in this report, the industry itself—together with its direct and indirect employees—actually cost Tennessee state taxpayers more than they provide. Our estimates provide an initial accounting of not only the industry’s benefits, but also its costs.

IGCC/CCS -- Federal and State Incentives for Early Commercial Deployment

Through its focus on incentives for the coal industry, this document provides one of the best summaries we've seen on subsidies to coal gasification, Integrated Gasification Combined Cycle (IGCC) technology, and associated carbon capture and storage (CCS) methods. Of particular merit are the state-by-state summaries of coal-supportive programs and policies. As the document was published four years ago, some program may have changed; however, the normal duration of subsidy policies suggests the vast majority remain in effect.

Phasing Out Federal Subsidies for Coal

The purpose of this report is to urge consistency in the development and implementation of federal administrative policies. Even as President Obama has pledged to phase out fossil fuel subsidies, the Federal Government prepares to establish limits on greenhouse gas emissions, and the Administration fosters a transition to a low carbon economy, some Federal agencies continue to have policies and programs that provide substantial subsidies for the construction, expansion, and life extension of one of the largest sources of greenhouse gas emissions in the U.S. - coal-fired power plants.

Data on Coal Industry R&D Spending on CCS

Despite industry advertising to the contrary, an analysis by the Center of American Progress determined that ACCCEs companies spend relatively few dollars conducting research on carbon capture and storage, among the most promising clean coal technology to reduce global warming pollution from coal-fired power plants. This technology would allow power plants to capture 85 percent or more of their carbon dioxide emissions and permanently store them underground in geological formations.

The Impact of Coal on the Kentucky State Budget

Rapid and dramatic changes in the world’s approach to energy have major implications for Kentucky and its coal industry. Concerns about climate change are driving policy that favors cleaner energy sources and increases the price of fossil fuels. The transition to sustainable forms of energy is becoming a major economic driver, and states are moving aggressively to develop, produce and install the energy technologies of the future. Long reliant on coal for jobs and electricity, Kentucky faces major challenges and difficult choices in the coming years.