Two straightforward concepts drive the inevitable marketplace defeat of nuclear power in most power markets: incremental innovation and lot size. People are quite clever in making many things, but we also frequently screw up. We learn by educated trial and error, and we get better bit-by-bit over time.

If we have many people working on a problem; and we have many chances to try something new and tweak it to make it work better, the probability of a successful outcome (increased durability, lower cost, better performance) goes way up. It's not because our initial trials are necessarily more successful in power storage than in fission reactions (even Tesla's recent storage product is hardly problem-free), but rather because we get so many more chances.

This, in a nutshell, is the structure of efforts to improve battery storage for electric power: huge experimentation on storage chemistry and business models (business models can matter as much or more than technical gains at particular stages of product development) across multiple related markets, and an ability to integrate small improvements into product cycles again and again. In combination, the pace at which power storage is becoming a competitive threat to nuclear (and to many other energy market incumbents) is accelerating.

Nuclear proponents agree with the general approach: they, too, want incremental and experiential innovation to improve their product. The idea is behind many of their public policy statements on the future role they want nuclear to play, and the concept that even though the first-of-a-kind reactors (FOAK) may be exorbitantly expensive, they pinky-swear that unit costs will drop sharply in later units (though this hasn't happened historically).

The structure of the nuclear power industry, however, is far less amenable to this type of innovation than are batteries. There are a small number of firms making a small number of enormously expensive reactors. The machines, and their related installations, are complex with many things that can go wrong. And the limited number of reactors being built are going in over a very long period of time, dampening innovative momentum. Costs of failure are quite high, both financially and in terms of potential damage to human health and the environment. This makes technical risk-taking imprudent, further constraining opportunities for innovation.

Industry efforts to overcome these limitations by streamlining regulation, reducing public oversight, and promoting larger production runs of smaller reactors may offer some benefits, but don't change the core competitive constraints. The differential in lot sizes between reactors and power storage devices remains overwhelming; and the ability to work small innovations into products across markets and time is dramatically larger in the power storage sector.

While nuclear reactors can also benefit from power storage (by running full tilt and banking the extra power to sell during peak demand), batteries able to handle much smaller scale loads are likely to come to market well before products big enough to facilitate reactor-scale storage. Instead, reactors will need to look to "bank" their surplus power in other ways -- such as through co-location with electricity-intensive primary industries like metal smelting or desalination. This is an old idea, but has not proven particularly successful. If the associated industry is also hugely capital-intensive (as it often is) and needs to run at full tilt to be economic (as it often does), the ability to dump only surplus power into the alternative use can be more limited than what is needed for these industries to serve as a "battery" for the reactor.

Here are some numbers to illustrate the competitive wall nuclear faces -- even assuming the myriad subsidies to the nuclear fuel cycle continue:

Nuclear power plant market size

930 Gigawatts - Nuclear generation that the Nuclear Energy Agency projects will be required by 2050 in their 2 degree warming scenario, comprising 17% of global electricity production. Of this, about 400 GW replaces the closure of existing units.[fn]Nuclear Energy Agency, Technology Roadmap: Nuclear Energy, 2015, p. 5.[/fn]

580 - 775 - Number of new reactors built to supply this target. Low-end of range assumes roll-out of 1600 MW Areva EPR; high end of range assumes 1200 MW Westinghouse APR. The reactor count is already significantly lower than what the NEA projected in their 2010 Technology Roadmap for nuclear, and worsening economics even for existing nuclear reactors make the 2015 projection optimistic as well.

$4,400,000,000,000 - Estimated investment over the next 35 years to build these reactors per the NEA estimates (p. 23). This figure includes few, if any, of the many government subsidies to the nuclear fuel cycle -- meaning that the real cost of this expansion would be much larger than $4.4 trillion.

35 years - Time period over which these reactors will be deployed in the NEA 2 degree scenario.

22 - Average number of reactors per year being built around the world over the 2015-2050 time frame modeled by NEA in its 2 degree scenario. The actual lot size per year will be smaller due to country-specific customization required, multiple reactor types, and multiple manufacturers. These factors all impede the technical and administrative learning that can occur to improve the competitiveness of the new plants.

100% - Share of reactors in NEA scenario that seem to be supported by significant government interventions to guarantee debt, invest capital directly, guarantee purchases of power, or support the fuel cycle in other ways.

0 - Number of repositories for high level nuclear waste currently operating in the world. There are one or two operating sites for centralized interim storage, but none for permanent disposal.[fn]World Nuclear Association, "Radioactive Waste Management," March 2015 update, accessed 7 May 2015.[/fn] The vast majority of the technical and economic risks for building and operating these facilities around the world is borne by taxpayers, not waste generators.

Battery market size

All of the markets below involve high value applications of portable power, where customers pay a premium for lighter, more durable, and longer battery life. While the technologies may not be identical to the storage approaches most applicable to power plant or distributed generation power storage, there is a great deal of spillover. The frantic pace of innovation in the sector, the huge amounts of revenue-supported private funds invested into technical learning and production improvements, and the common performance goals across many of the market sectors all support the idea that the combined demand from the sectors below are quite relevant to power storage in the electricity sector.

Note as well that battery storage in the power sector can support multiple power generation technologies, not just solar; and can substitute for existing cost centers such as emergency backup power. These attributes increase the competitive threat storage plays to nuclear (since multiple technologies open more pathways to cost reductions) and reduce the cost barriers for commercial or industrial customers to invest in battery storage since they need to pay for backup capacity anyway.

293,245 - Number of plug-in electric vehicles, each of which contains multiple batteries, sold worldwide during 2014.[fn]http://www.hybridcars.com/top-6-plug-in-vehicle-adopting-countries-2014/, accessed 6 May 2015.[/fn] The pace of adoption is accelerating.

148,000,000 - Number of laptop computers shipped by original device manufactures (the firms supplying most of the major brand names) in 2013. [fn]http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_laptop_brands_and_manufacturers, accessed 5 May 2015[/fn]

230,000,000 to 285,000,000 - Estimated number of tablet computers shipped during 2014.[fn]http://tabtimes.com/resources/the-state-of-the-tablet-market/, accessed 5 May 2015.[/fn]

1,300,000,000 - Number of smart phones shipped during 2014.[fn]http://www.idc.com/prodserv/smartphone-market-share.jsp, accessed 6 May 2015.[/fn]

6,800,000,000 - Number of cell phone lines in the world as of February 2014, nearly all of which have an associated mobile device and battery.[fn]http://qz.com/179897/more-people-around-the-world-have-cell-phones-than-ever-had-land-lines/, accessed 5 May 2015.[/fn]

14 seconds - Amount of time for the lot size of batteries produced for the above devices alone to equal the number of nuclear reactors that would be built over the next 35 years under the NEA scenario.

So which sector would you bet will have the most significant technological improvements and cost reductions over the next two decades? Arnie Gunderson, a frequent critic of the nuclear industry, framed the issue nicely in a recent Forbes magazine article on Tesla's threat to nuclear:

[T]he nuclear industry would have you believe that humankind is smart enough to develop techniques to store nuclear waste for a quarter of a million years, but at the same time human kind is so dumb we can’t figure out a way to store solar electricity overnight. To me that doesn’t make sense.

His sentiment matches my take on meetings I attended last year at the IEA on finalizing the updated nuclear technology roadmap report. The majority of participants were nuclear proponents interested in expanding the number of reactors and the market share of nuclear power.

The belief that nuclear was the only viable mechanism to provide large scale, low-carbon power was also widespread. This perspective was particularly striking to me given the long time horizon being discussed. The scenarios included new plant starts through 2050, which, with operating lives of at least 40 years means the solutions being proposed will span three quarters of a century. The technical change that will occur during this period will be stunningly large -- think how much has changed since 1939, 75 years ago. It is hard to believe that nuclear's main competitive advantage over other low-carbon resources (i.e., it is not intermittent) won't be solved during the next few decades; and if it is solved, I'd hate to have national governments guaranteeing trillions of dollars of nuclear debt. Whereas the nuclear buildout scenarios involve roughly 1,000 new reactors, the pressure for improved power storage will be coming from many different sectors (primarily consumer electronics and phones, electric vehicles, and power storage) with unit counts in the billions. The range for innovation, incremental technical change and improvement, and cost reductions will be vastly larger than in the nuclear sector.

I mean, why should the rest of us worry that Iranian consent to an agreement with invisible clauses won't actually be followed? Greg Jones of the Nonproliferation Policy Education Center has been tracking the Iranian nuclear effort for quite some time. Probably

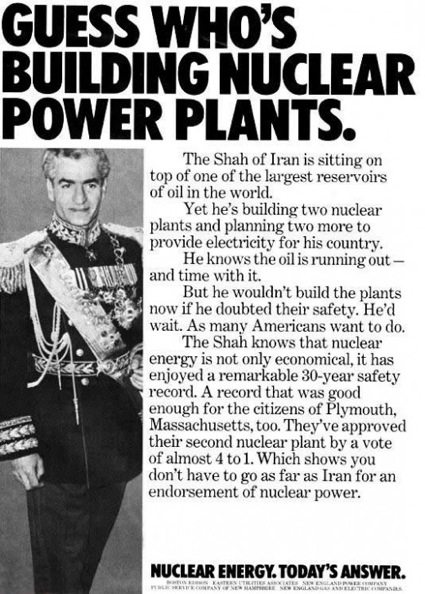

I mean, why should the rest of us worry that Iranian consent to an agreement with invisible clauses won't actually be followed? Greg Jones of the Nonproliferation Policy Education Center has been tracking the Iranian nuclear effort for quite some time. Probably  And just for fun, here's an ad from the pre-revolution days in Iran. The ad clearly illustrates the US role in promoting nuclear power in Iran as though it were little more complicated than plopping down a windmill in a farm field somewhere. Nuclear is presented as a resource that, with a little government help of course, can soon come to a neighborhood near you.

And just for fun, here's an ad from the pre-revolution days in Iran. The ad clearly illustrates the US role in promoting nuclear power in Iran as though it were little more complicated than plopping down a windmill in a farm field somewhere. Nuclear is presented as a resource that, with a little government help of course, can soon come to a neighborhood near you.

Some of the key points:

Some of the key points: