1) Solar parity and my cousin Jeff. Congrats to Jeff Koplow, an energy researcher at Sandia National Labs, for being named the inaugural recipient of the Innovator in Residence Fellowship awarded by DOE's SunShot Initiative. He'll lead a multi-disciplinary team in attacking key limits in current PV systems.

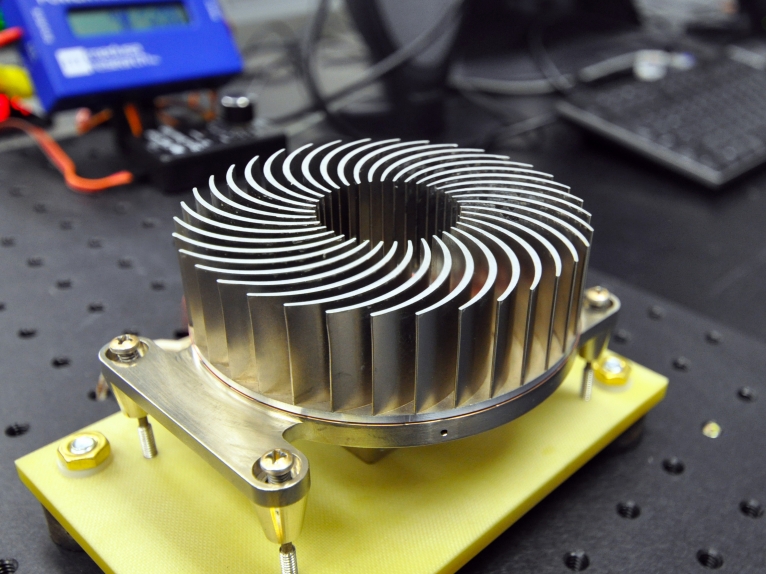

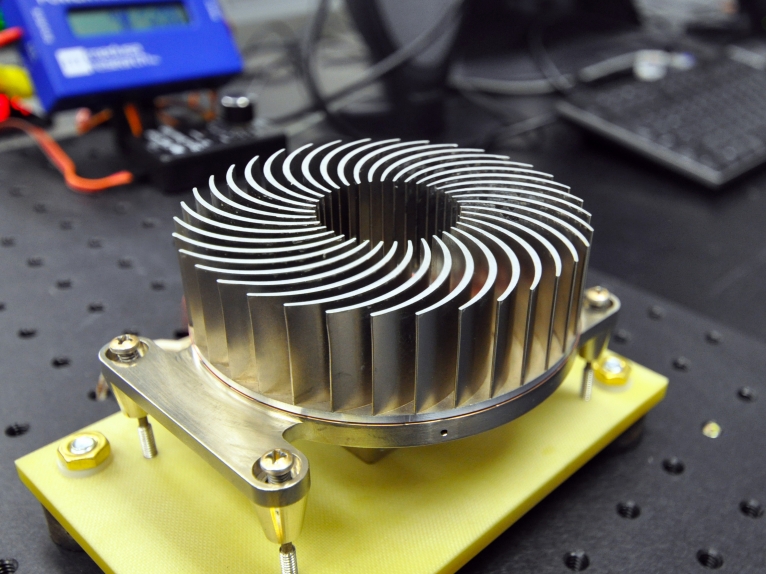

Jeff's been working on energy innovation for a very long time, and some of  his earlier inventions offer large benefits to the US energy sector. These include the Sandia Cooler, a much more efficient way to cool heat exchangers and CPUs; and Twistact (winner of an Outstanding Technology Development Award), a new way to connect turbines to the gear box without a sliding contact, electrical arcing, or the need for rare earth metals.

his earlier inventions offer large benefits to the US energy sector. These include the Sandia Cooler, a much more efficient way to cool heat exchangers and CPUs; and Twistact (winner of an Outstanding Technology Development Award), a new way to connect turbines to the gear box without a sliding contact, electrical arcing, or the need for rare earth metals.

2) Fossil fuel subsidy reform update from COP21 (and nukes too). "The Beginning of the End of Fossil Fuel Subsidies," a blog update from Paris by staff of the Global Subsidies Initiate, summarizes some of the interesting and promising developments on fossil fuel subsidies at COP21. Read their take here; there is real progress.

Here's one of the (albeit non-scientific) benchmarks I use to gauge progress on subsidy reform:

- 25 years ago, almost nobody outside of NGOs would talk about energy subsidies. (I once had a potential faculty advisor for my update on US energy subsidies ask why I didn't want to work on something "useful").

- 15 years ago, heads of environmental and public health ministries would willingly talk about energy subsidies.

- As of about 7 years ago, heads of financial ministries would willingly talk about energy subsidies.

- Today, even many heads of state willingly talk about energy subsidies -- at least fossil fuel subsidies. Conversations about subsidies to the nuclear fuel cycle will have to wait another few years, I suppose.

For a report on the push for massive new subsidies to nuclear at COP21, here's a summary from Michael Mariotte of NIRs.

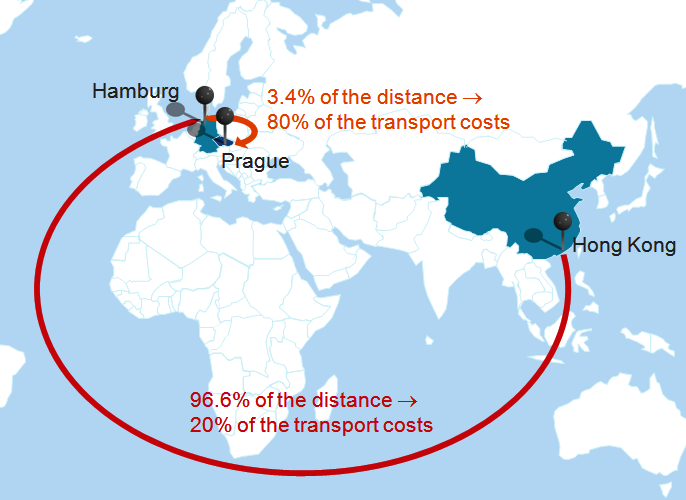

3) Addressing tax exemptions to fuel used in international shipping. Subsidies that almost nobody sees or thinks about can be particularly distortionary. In darkness, the biggest mushrooms grow -- or something like that. Wholesale exemptions of fuels used in international ship, air, and rail transport from taxation is one example of issue (the subsidy even made my top 10 most distortionary energy subsidies list).

Particularly for activities that cut across multiple countries, the options available to correct the problem can be heavily constrained by pre-existing international agreements. Those agreements were often developed to with trade or sovereignty issues in mind; transparent pricing of natural resources was generally not a factor.

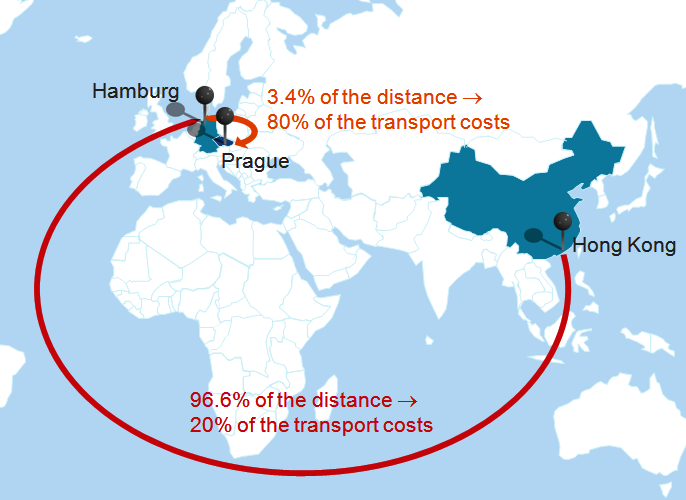

One possible solution to this conundrum is put forth in a recent working paper ("Drying up tax havens-A mechanism to unilaterally tax maritime emissions while satisfying extraterritoriality, tax competition and political constraints") by Dirk Heine, Susanne Gäde, Goran Dominioni, Beatriz Martínez Romera, and Arne Pieters. As the title implies, there are a fair number of hurdles any solution needs to meet. The authors focus on using cargo as the tax base rather than the fuel itself; and structuring the tax levy formula such that higher efficiency vessels end up with a lower tax. To avoid distorting port-use decisions, transhipped cargo would not incur the tax. There is contact information for the authors in case any of you have additional suggestions or ideas. There is also a summary description of their plan here, which provides a quick overview of the approach.

4) Limiting export credit support for coal plants. Export credit subsidies have been an area much talked about, but too often ignored when subsidy reform plans are put forth. The subsidies are often tough to value, but can be quite large and tip high risk projects in environmentally-sensitive regions of the world from "no-go" to actionable. The subsidies generally work by offering direct loans or guarantees at below the market rates that firm or industry would normally be able to receive. The  support may also generate an incremental subsidy by enabling high risk enterprises to utilize higher debt-to-equity ratios than would otherwise be possible, reducing the project's weighted average cost of capital.

support may also generate an incremental subsidy by enabling high risk enterprises to utilize higher debt-to-equity ratios than would otherwise be possible, reducing the project's weighted average cost of capital.

Against this backdrop, an agreement among OECD nations to significantly reduce their ability to finance the export of low-efficiency coal-fired power plants and equipment is a very positive step. Read the agreement here.

5) Charles Koch, one of the Koch brothers, argues for subsidy elimination. It's hard to imagine the whipsawing that must have been ripping through Charles Koch as, year-after-year, his push for small government, free market libertarianism ran smack into his affinity for the array of special government subsidies that have benefited his oil, gas, and now paper operations for generations. Maybe his latest book, Good Profit: How Creating Value for Others Built One of the World's Most Successful Companies, is his effort to finally reach an internal cease fire.

To his credit, Koch does acknowledge he's been a subsidy beneficiary. And, I do agree with a core premise of his criticism: that our convoluted and complex system of subsidies tends to favor the well-connected and the wealthy, replacing economic viability with political connections in the selection of markplace winners. Lower income quintiles clearly need the support more than the rich. Similarly, on the corporate site, the new companies that will create the jobs and industries of our future are generally too small to have lobbying arms.

How big are subsidies to Koch-related firms? This article pegs the figure at about $200 million since 1990, based on data from DC NGO Good Jobs First. I consider this a low estimate, probably really low. The Good Jobs First data sources don't always pick up subsidies through credit or insurance markets. Non-standard ones, such as the "black liquor" tax break that many of the paper companies tapped into by stretching a pre-existing rule targeted as new fuels, are also often missing. Data on privately-owned Koch subsidiary Georgia Pacific are hard to come by, but given its scale, this tax break alone could have exceeded $200m. In fact, this analysis estimated black liquor subsidies to Georgia Pacific just in 2009 at $1 billion. Finally, the private nature of Koch means commonly-available tax breaks to oil and gas may not show up in the $200m figure either.

The point here isn't to attack Koch for saying corporate welfare should be eliminated. The subsidy trough is a crowded one, so the limiting the push for reform only to those who are "pure" enough not to have been subsidized would be foolhardy. If Charles is serious about finally reforming subsidies, this is a good thing. Properly done, the changes would improve the economic vitality of the country going forward.

But one should not take the input of Koch or other current beneficiaries blindly. It is vital for anybody working on subsidy reform to read the small print on any proposal to be sure there are no surprise gaps. Varying definitions (or more perjoratively, a definitional sleight-of-hand) can coincidently eliminate the subsidies to competitors while keeping their own.

his earlier inventions offer large benefits to the US energy sector. These include the

his earlier inventions offer large benefits to the US energy sector. These include the

support may also generate an incremental subsidy by enabling high risk enterprises to utilize higher debt-to-equity ratios than would otherwise be possible, reducing the project's weighted average cost of capital.

support may also generate an incremental subsidy by enabling high risk enterprises to utilize higher debt-to-equity ratios than would otherwise be possible, reducing the project's weighted average cost of capital.

International agreements are always political. The wording is often vague, allowing countries to "agree" on a document that sometimes means very different things to each of the signatories. In some cases, this vagueness allows at least some steps to be taken on important international issues, with scrutiny and compliance rising over time as institutions, measurement, and systems of accountability are established.

International agreements are always political. The wording is often vague, allowing countries to "agree" on a document that sometimes means very different things to each of the signatories. In some cases, this vagueness allows at least some steps to be taken on important international issues, with scrutiny and compliance rising over time as institutions, measurement, and systems of accountability are established.