The acrimony on increasing the debt ceiling is hitting a fevered pitch, and the likelihood of a technical default on US debt is unfortunately becoming a larger possibility each day. I wondered whether there was anything one could learn by looking at the personal financial filings of some of the people opposed to raising the ceiling and/or incorporating increased revenues in stabilizing the country. Does the way they run their portfolios match or conflict with what they are advocating at the national level? Are there direct or potential conflicts of interest?

Private spending as a window to public positions?

To do this, I pulled the financial disclosure forms of four individuals: Rep. Michele Bachmann (R-MN), Rep. Eric Cantor (R-VA), Rep. Ron Paul (R-TX), and his son, Sen. Rand Paul (R-KY). I looked at their most recent filing (2009 or 2010), as well as the first year they were a member of Congress to see any major changes. All have been rather vocal opponents of larger government, increasing the debt ceiling, or of including policy changes that boost revenues, even if those changes are merely to eliminate tax breaks rather than increasing the marginal tax rate overall. All of the Members examined are Republicans, simply because the opposition to avoiding default by increasing the debt ceiling has mostly been a Republican position. Perhaps others can dig into the portfolios of some on the Democratic side of the aisle to assess whether their investment style highlights concerns as well.

To begin, it is a wonderful thing to be able to actually see the financial condition and positions of the people who govern us. While the reports (I pulled my copies from opensecrets.org) are not perfect, they do provide an important check to corruption and conflicts of interest. They tell us the assets our officials own, as these can influence what issues they view as important and how they want them to come out. The disclosure reports tell us what the Members buy or sell and when, important in evaluating potential misuse of Committee positions or insider information. Finally, they can tell us if particular Members are facing financial distress or large declines in their wealth, factors that could make them more vulnerable to improper activities. Imagine being able to see similar information for world leaders such as Vladimir Putin, Robert Mugabe, or Hosni Mubarak.

Now, on to their portfolios.

1) All four are richer than the median US family. While many citizens struggle to stay out of debt, all four had a positive net worth. Even at the low end, this was comparable to or higher than the net worth ($120k in 2007) for the median US household (see Table 720). The financial disclosure reports present only range values for each holding, resulting in an ever-larger spread between high- and low-end estimates as the number of positions increase. Thus, Rep. Bachmann has a net worth that could be a low as $112k, or as high as $1.7million, fifteen times higher. Sen. Rand Paul is in a similar situation, with a net worth spread of $129k to $1.48 million. Cantor and Ron Paul are in a different category, with net worths of $2.2 - $7.5m and $2.3 - $5.1m respectively. While certainly not on the order of wealth that Sen. John Kerry (D-MA) has ($183 - 295m), the four still do have more of a financial cushion to fall back upon than many Americans.

2) Despite positive net worth, all would see large financial losses following a US default. Although the technical default would initially apply only to US Treasury securities, the default is widely expected to cause severe dislocations in nearly all other asset classes. This would be similar to the meltdown in 2008, when equities large and small, domestic and foreign, all took a hit. So did bonds of nearly all types and grades. Real estate went into free fall, and illiquid partnership interests had a difficult time finding buyers at all. Even energy plummeted as the recession took a bite out of demand.

The assets held by three of the four members evaluated fall into one or more of the asset categories battered by the subprime mortgage-triggered recession. These members would be expected to see large investment declines in a Treasury default as well. Ron Paul is the most buffered (more on that below), though even precious metals fell during the last recession as gold was lumped in with other commodities and inflation risks that play a role in investing in gold declined.

It is actually a good thing for Members of Congress to see personal financial losses if they screw up though; it aligns their interests more closely with ours, and increases the chances they will work successfully to avoid defaulting.

3) Is anybody betting against the US?

I looked at their current portfolios to see whether there were any positions that would be likely to do well in the case of a default or near-default. In theory, this could generate a financial interest misaligned with the average voter.

There were a few candidates for further evaluation: shorting Treasuries, concentrated positions in precious metals, and high international holdings.

Shorting treasuries. Eric Cantor has been excoriated in a number of places (here's a link to one article on Salon) for shorting Treasury bonds. He holds between $1-15k in Proshares Trust Ultrashort 20+ year bond fund. This holding is certainly a problem, since it will do well if Treasuries do poorly. However, the WSJ points out that Cantor is also long in Treasuries in his retirement account and his spokesperson told that Journal that the short position merely hedges part of that exposure. If the Ultrashort fund moves 200% opposite the direction of Treasuries (this is its mandate), his short position is at most $30k. Even incorporating the leverage, however, his long positions in Treasuries were larger ($50-100k in Vanguard TIPS [Treasury Inflation Protected Securities] plus $1-15k in Vanguard Short-Term Treasury Fund). TIPS are likely to see declines during a default. Thus, even in the very unlikely event that a default will not spread contagion beyond the Treasury bond asset class, Cantor is a net long and will suffer more from a default than he will gain.

That said, the Ultrashort products really don't provide much of a useful long-term hedge strategy, and his position isn't large enough to provide any significant cover portfolio-wide. Further, they sure create the appearance of a conflict of interest. That appearance would turn into a real one should Cantor sell the position during a period of uncertainty at a gain. Given these factors, the position seems more trouble than it is worth.

Stocking up on precious metals. In times of great uncertainty, precious metals surge. This is happening now, and metals would most likely spike still further following a default in the world's reserve currency. Of the four Members evaluated, this outcome would mostly benefit Ron Paul. He holds large concentrated interests in a slew of mining companies and metal funds, heavily focused on gold. The largest of his positions are Agnico Eagle Mines (international gold mining, at $100-250k), AngloGold Ashanti ($100-250k); Barrick Gold ($250-500k); Eldorado Gold Corp ($50-100k), Gold Corp Inc. ($500-$1,000k), Golden Star Resources ($15-50k), IAM Gold Corp ($100-$250k), Kinross (gold, $15-50k), Mag Silver Corp ($50-100k), Newmont Mining ($250-500k), Pan American Silver ($50-100k); Silver Wheaton Corp ($50-100k), Virginia Mines ($15-50k), and many smaller positions in precious metals firms. The elder Paul also holds a number of real estate properties, and at least one fund betting on market downturns (Prudent Bear Mutual Fund, $1-15k).

While his concentrated positions in gold may derive from his ideological goals of getting rid of the Fed and shifting back to the Gold Standard rather than a desire to cash in on a US default and downturn, it is nonetheless quite plausible that he would benefit substantially from such an occurrence. (As an aside, gold mining is a nasty business; it would be interesting to know whether Paul takes any position on which firms he puts his money in; and whether he supports the "No Dirty Gold" standards).

While the economic malaise following a US default would certainly affect his real estate and mutual funds, of the four Members, Ron Paul has the greatest likelihood of being a net winner financially from the turmoil.

His son Rand has much less wealth than Ron, and is invested via widely diversified mutual funds and tax-advantaged college savings plans. He also derives income from real estate holdings.

Eric Cantor has concentrated holdings in range of natural resource firms (more on this below), but more focused on energy than in precious metals. Michele Bachmann is similar to Rand Paul with primarily diversified funds and little to gain financially from a flight to gold or economic instability.

International stocks and currencies. One might theorize that declining power of the US following a default would depress US equities, and that foreign holdings would do much better. This is overly simplistic in my view. Large US firms have substantial earnings from outside the US; and large foreign firms have substantial earnings within. Further, there is no magic firewall between US debt markets and global capital markets. The uncertainty will spread widely across asset classes. Even if foreign positions fell a bit less than US ones, they would still fall sharply, leaving the long investor worse off.

Nonetheless, it is interesting to note that three of the four Congress members evaluated have substantial global diversification (Rand Paul doesn't provide enough specifics on which mutual funds he's in to tell). There is no "Buy America" in force when it comes to their own investments. For Ron Paul, this is through a wide array of international mining operations. Of Rep. Bachmann's 13 mutual fund positions, five of them are all or largely international, including her largest mutual fund position (Capitol World Growth & Income Fund, $50-100k). Rep. Cantor owns mostly larger firms with a combined domestic and international presence, but also a couple of focused non-US funds: Morgan Stanley Emerging Markets ($1-15k) and Claymore ETF Trust 2 (investing in Chinese technology firms, $1-15k). I did not see any significant investments in foreign currencies or bonds, though positions may be embedded in some of the funds owned.

Overall, the international diversification provides Members with some protection against a weakening dollar, but is unlikely to provide shelter following a Treasury default.

4) Impediments to reforming tax subsidies. All of the four have looked unfavorably at including revenue increases in any deal to boost the debt ceiling. This includes eliminating at least some of the many distortionary tax breaks that now populate our tax code for the benefit of constituent groups or particular social objectives.

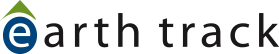

As documented in Pew's Subsidyscope project, Treasury losses through tax expenditures are now almost as large as discretionary spending (see Figure 1 below, based on GAO data). These are selective tax breaks, often politically motivated, to support specific industries or individuals. Their impact is to force higher taxes on the rest of us (or to run higher deficits if the lost revenue is not made up elsewhere), and to generate an uneven competitive playing field as some market partcipants pay lower taxes than do competitors with substitute goods or services.

Fixing these problems would have enormous fiscal and competitive benefits for the country. There are, of course, always some losers from reform. These losing firms are often large political donors, which is a key reason fixing the problems is so hard. But nearly $1 trillion in tax breaks can no longer be ignored given the fiscal situation the country is in.

Figure 1: Discretionary Outlays vs. Tax

Expenditure Estimates in Constant Dollars

($ billions)

Total Discretionary Outlays

Sum of Tax Expenditure Estimates

Source: GAO analysis of OMB budget reports on tax expenditures, FY1982-FY2009.

Note: The tax expenditure data from FY2000-FY2009 can also be found

in Pew's Tax Expenditure Database (Subsidyscope has not adjusted the estimates for inflation).

Subsidies to energy and metals industries. Both Ron Paul and Eric Cantor would suffer financially from eliminating tax breaks to energy and mining industries. Because of his skewed portfolio, I expect the costs would be larger for Paul than for Cantor. Affected provisions include percentage depletion allowances that allow tax deductiosn in excess of actual investments; antiquated rules for hardrock mining (this includes gold, silver, bauxite and uranium, among others on federal lands) land rights, royalties, and cleanup; and a slew of tax breaks for oil, gas, and ethanol.

These tax breaks are not limited to domestic producers. Percentage depletion subsidies normally apply to foreign mines if owned by a US taxpaying entity. International operations also benefit from dual capacity rules that sometimes allow royalties on energy or mineral extraction to be disguised as foreign taxes, earning a credit rather than a mere deduction from US taxes owed.

Ron Paul has few energy companies, but Cantor has quite a few single asset positions in both mining and energy: Archer Daniels Midland (ethanol and corn, $15-50k); Cameco (uranium mining, $1-15k); Consolidated Edison (power, $15-50k); Dominion (electricity and natural gas, $1-15k; one of his larger campaign donors); Georgia Power (debt, $1-15k); Newmont Mining ($15-50k), Rio Tinto (mining, $1-15k), San Juan Basin Realty Trust (oil and gas, $1-15k); Schlumberger (oil field service, $50-100k); SPDR Metals & Mining ETF ($1-15k).

These positions may be one reason why Cantor has been lukewarm at best on eliminating misguided subsidies to oil and gas. However, his exposure to real estate, particularly in Virginia, is much larger than his exposure to energy firms. So too are his family's holdings in firms for which his wife serves as a director (Domino's Pizza, $1-15k in stock, $100-250k in options; Media General, $1-15k in stock; $250-500k in deferred stock compensation).

Subsidies to mortgage interest, college funds, and retirement funds. All of the Members evaluated have benefited from at least one of these tax breaks over time. Cantor's wife works in the college fund industry, and their portfolio is peppered with 529 plans. Rand Paul also has a few. All have tax-advantaged retirement accounts; two have had residential mortgages. While these are tax breaks that I also like and benefit from, it is useful to remember that they also tend to disproportionately benefit wealthier people. When members of Congress push to cut housing support for the poor, but fight tooth and nail to protect mortgage interest deductions -- even for very expensive or second homes -- one can quickly see why ignoring the revenue side makes no sense.

Subsidies to dividends and capital gains. With positive net worth that is held not only through home ownership (a main store of wealth historically for most Americans) but in stocks as well, all four benefit from lower tax rates on stock dividends or long-term gains from selling appreciated stock positions. These tax rates can be half that paid on ordinary income.

5) Use of debt in personal finances. I was interested in how these individuals used debt in their personal lives and whether there were any disparities between personal use of debt and their positions on public debt.

Ron Paul reported no debt on his last financial disclosure form, though did carry two mortgages in 1994, his first year filing. One of those mortgages was $50-$200k, issued by Countrywide Funding Corporation. Countrywide subsequently became the poster child for improper mortgage practices, including offering VIP rates to members of Congress. (Note: there is no indication that Rep. Paul benefited from one of these sweetheart deals, however.)

Eric Cantor's debt load was 10% or less of his family assets. Michele Bachmann had two loans, a mortgage in the amount of $250-500k; and a business loan for $100-250k. This generated a debt level commensurate with 36-41% of her assets. For Rand Paul with roughly $200-500k in commercial mortgages, his debt level is 29-32% of his assets.

Comparisons with national debt are a bit tricky. Debt is approaching 100% of our GDP, but GDP is a flow-measure, not a stock of assets similar to the values included in the personal financial disclosure forms. While the share of net assets would be lower, the scale remains worrying.

Still, it is useful to note that all of the Congressional members here relied on debt at one point in their life. Further, this reliance on debt might be even more striking were we to look at their campaign finances, particularly after their first runs for Congress, rather than just their personal accounts. Clearly, they all have seen that debt can be useful; it is merely ensuring that the levels stay in control.

6) Other general thoughts on the financial disclosure forms.

- Aside from making a general point about the gold standard, from a financial diversification perspective Ron Paul's portfolio structure seems insane. He's had a grand run recently with the global run-up in gold and silver prices. But if I were his family member, I'd be working hard to get him to do some serious asset diversification.

- Michelle Bachmann has so many mutual funds that some of them are likely overlapping with each other in holdings or conflicting in mandates. This overlap often results in index-like returns but with active management fees. More to that point, most or all of the funds she holds seem to be actively managed rather than passive ETFs or broad index funds. The active funds have higher fees, higher tax costs from churn, and over the long-term often under-perform the very inexpensive ETFs.

- Bachmann's first filing (for 2005-06) had a detailed listing of honoraria paid to both her and her spouse. These are nowhere to be seen in the most recent filing, though it would be a surprise if such engagements had stopped. All that shows up now is a single line item titled "spouse salary," with "N/A" listed for amount. This seems a large gap in the reporting framework for all Members, as only in an imaginary world would large compensation sources to a spouse have no impact on the decisions or views of the Member.

- Eric Cantor's portfolio structure seems to me to be quite haphazard, with a mix of fairly large individual stock positions, mixed in with assorted funds. Most of the funds held in his first filing in 2000 were from Goldman Sachs. Quite a few Goldman funds remain today. Goldman is not normally viewed as a mutual fund leader, so the concentration there is financially puzzling. Politically, there seem to be employment and campaign ties however (Goldman was the fourth largest donor to his campaign and some of the listed investments came from a Goldman Sachs retirement plan). Also puzzling is Cantor's decision to proceed with holding fairly large individual stock positions in a domestic equity portfolio that doesn't seem fully diversified across sectors. Perhaps the positions are legacy, or part of an actively managed account where the manager believes he or she can outperform the benchmarks even on large and thoroughly researched domestic equities. Good luck with that. Under-performance is far more likely, especially after manager fees, trading costs, and taxes. The large, single positions also give a much greater perception of conflicts of interest than simply owning funds or ETFs.

- Despite fairly substantial wealth, there is not much in the way of hedge funds or private equity holdings in the Holder or Ron Paul portfolios. This may make them more open to eliminating tax breaks to hedge fund manager's "carried interest", though political contributions from financial firms would obviously pressure them in the opposite direction.

- There is not much clarity on the non-traded partnership and real estate holdings that many of the Members have. The dollars are sometimes quite large, but it is difficult to assess how these positions might bias Members without having further information on the deals and who else they involve.

Overall, three of the four Members evaluated are likely to suffer enough in a downturn that their interests in avoiding default are aligned with the rest of us; the fourth will probably see large losses as well in a global contagion. All benefit significantly from specific tax breaks to portfolio holdings, and this may be an impediment to their moving forward with logical and beneficial corrections to our tax expenditure budget. That would be unfortunate.

UPDATE - December 27, 2011

In addition to betting against the country with their portfolios, Congress has often been attacked for using inside information they have on firms and pending legislation to profit in their market trading. A recent review (summarized in this Boston Globe op-ed) by Andrew Eggers at the London School of Economics and Jens Hainmuller at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology suggests that if Congressmen are investing based on insider information, they are doing a poor job of it. Analyzing the entire portfolios of members, the two found that:

members of Congress generally perform no better than ordinary investors. Over the 2004-2008 period, the stock portfoio of the average member of Congress underperformed the market by 2 to 3 percent per year. Put another way, in a five year period during which the market lost around 20 percent of its value, the average Congressional portfolio lost 30 percent. Even individuals whom Schweizer[fn]Author Peter Schweizer, who argued that insider trading within Congress was widespread in his book "Throw Them All Out".[/fn] singles our for suspicious trades would probably have been financially better off if they had replaced their stock portfolios with a passive index fund.