1) Don't Prop up USEC. Henry Sokolski of the Nonproliferation Policy Education Center and Autumn Hanna at Taxpayers for Common Sense weigh in at the National Review Online on a proposed $2 billion dollar loan guarantee to finance new enrichment facilities for the United States Enrichment Corporation (USEC). USEC is the privatized residual of the government-run Uranium Enrichment Enterprise that ushered in the US nuclear era. In Another Solyndra: Ohio Republicans join the energy-subsidy racket, they argue that politics are leading the push of put taxpayer money at risk despite an extremely poor business case.

The business case should matter far more than it seems to in Washington. And this is so not just for each specific subsidy recipient, but also for how, in the aggregate, these interventions distort price signals and market structure overall.

With so much focus on solar subsidies, it is useful to point out that even if USEC doesn't get the guarantee in the end, they've already scored up to $300 million in federal money to "help USEC reduce the technical problems that forced DOE to reject USEC’s original application" for a Title 17 loan guarantee. That's bigger than the face value of many of the loan guarantees granted to renewable borrowers.

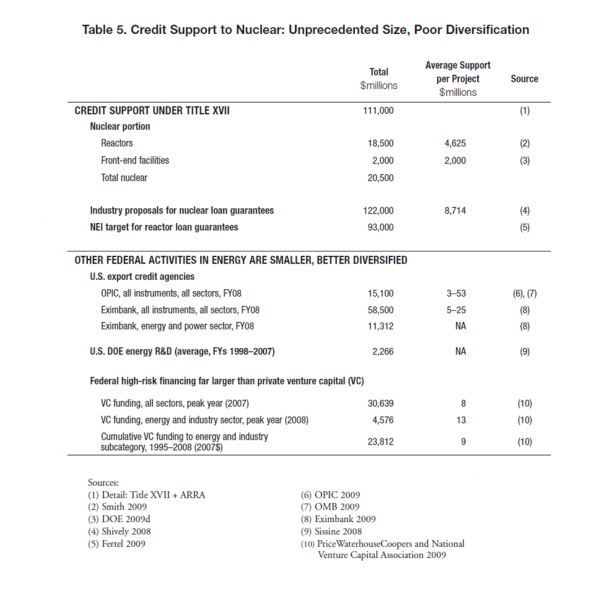

2) Anybody got a light? The effort to get the blaring light of fiscal conservative oversight now shining on Solyndra directed at least a tad towards the Vogtle nuclear deal proceeds on the dual tracks of litigation and legislation. Legal action by the Southern Alliance for Clean Energy (SACE) and Taxpayers for Common Sense to expose the terms of the loans continues, as DOE produced only heavily redacted documents in response the last FOIA request.

Of particular interest to SACE is information revealing whether company officials played an inappropriate role in shaping the terms of the loan guarantee. Based on the limited information produced, it appears that the power companies had to put almost no skin in the game, promising to pay a credit subsidy fee of possibly as little as 0.5 or 1.5 percent of the total loan guarantee.

House Democrats have been pushing for greater oversight legislatively as well, with a letter drafted by Rep. Henry Waxman (D-Calif.) and co-signed by Reps. Ed Markey (D-Mass.) and Diana DeGette (D-Colo.) to Chairmen Fred Upton (R-Mich.) and Cliff Stearns (R-Fla) of the House Energy and Commerce Committee. The letter notes that while they support a broadening of the Solyndra review to include 27 loan guarantees for renewable energy (something that has already been implemented), $10 billion in conditional guarantees to nuclear projects should also be included. This follows up on a similar push by letter co-signer Ed Markey last month.

In my book, this one is simple: if you aren't willing to look at potential conflicts of interest and corruption in all of the projects, don't call yourself a fiscal conservative.

3) Cash is cash, or don't cry when we invest your money abroad. Fisker Motors, recipient of a $529 million loan from the US DOE, is doing what any corporation does: it tries to find capital at the lowest possible cost and deploy that money however it sees fit to meet its own internal objectives. In this case, that means putting funds into manufacturing jobs abroad (or, per the input from Media Matters below, using the funding domestically to free up other funds to finance foreign manufacturing jobs). Oops.

On the other hand, as a major debtor to the firm, wouldn't taxpayers want Fisker to increase their chance of success as much as possible? Or, if you want to see electric vehicles enter the marketplace, wouldn't you want to maximize operational flexibility as well? I suppose that's the problem with having multiple objectives (is the loan for making jobs in the US or for trying to develop a new energy technology?).

Media Matters points out that the overseas construction was known prior to the loan guarantee being approved, implying this controversy is merely a manufactured issue. I disagree. The example underscores the core point that promoters of big federal subsidies too often ignore: in a global economy, building an industry from scratch doesn't mean it will all (or even mostly) be built here.

4) Risk is risk, or don't cry when bankruptcy or dilution come to call. The time for pricing risk is before you provide the credit. Happy talk about guarantees not really being subsidies (yes, we're talking about you, Dick Myers) should always be ignored by taxpayers and Congressmen alike.

A. The Belly-Up Club: Beacon Power becomes member number two. Flywheel producer (for bulk power storage) went belly-up today. Taxpayers were on the hook for $43 million. This, and Solyndra, will be good tests for the claims put forth by program promoters in years past that recoveries in bankruptcy will be substantial. Let's hope so.

Recoveries aside, expect more members in the Belly-Up Club soon. If we take the loan guarantee program to be what it really is -- investments with risks similar to venture capital or start-ups, expect failure rates of around 30-40%. If you expand the outcomes to include failure plus no return, we're up to 70-80% of the pool, according to Harvard Business School senior lecturer Shikhar Ghosh. Since Ghosh is talking private firms, and the incentive alignment within the Title 17 program between managers and the long-term performance of the firm is much worse, I'm expecting loss rates within the funded portfolio to be even larger absent big changes in the market (e.g., implementation of a large carbon tax).

B. Diluting the feds. Andrew Stiles raises concerns at the National Review Online that the restructuring of financing for Solyndra prior to its bankruptcy, a process that subordinated the Treasury's position in any subsequent bankruptcy, was illegal. He links to a series of e-mail chains on the restructuring, which are quite interesting in their own right:

- Discussion of subordination starts on PDF page 14.

- Page 21 notes that since July 2010 DOE was refusing to provide information on the Solyndra loan guarantee even to Treasury (which, of course, was backing the financing). This type of behavior underscores the concerns I had with program transparency and accountability back in 2007.

- Page 22 indicates that Lazard was the firm providing independent review to DOE, perhaps of the original deal or perhaps only for strategic options for Solyndra at that point in time. There has been very little visibility on who the financial advisors to DOE have been on the Title 17 program, and therefore on the real or potential conflicts of interest these advisors may have. This is a problem.

- Page 29 raises the intriguing possibility that investors may have been interested in keeping Solyndra alive longer to allow them to strip more assets from the firm (thereby reducing the government's collateral). Artificially high discounting of accounts receivable was one area mentioned.

While the lawyers will toil back and forth on the legality of subordination under the Title 17 authorizing legislation, to a great degree (and assuming there was no fraud or gross negligence within the government in the restructuring) it seems besides the point. If the government wants to do high risk investments, those investments go bad with surprising regularity. Any new money won't go in at the old terms. Either accept the risk of dilution, or don't play in the market.