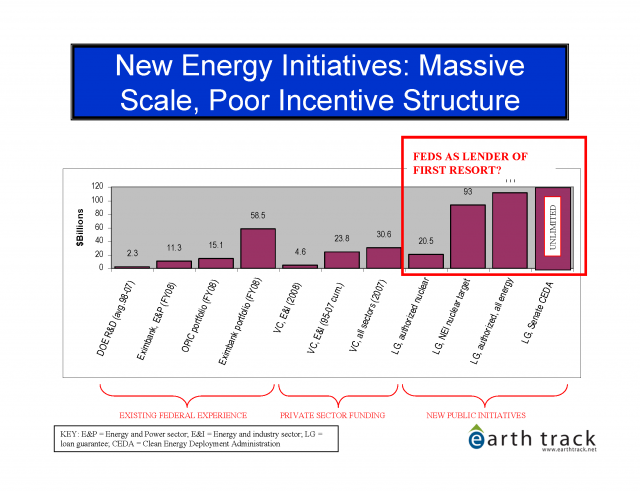

First, a disclaimer of sorts: as I've stated many times, I think the large scale credit support to private energy enterprises is a bad idea and not likely to end well. That said, I also think that the dynamics of how credit support is provided is an important issue for evaluation for many areas of policy; a start of that discussion is below.

While much of the discussion on the US Department of Energy's credit support to new nuclear reactors and other energy technologies refers to "loan guarantees," this is only part of the story. The statute authorizing this support also requires that where the federally-guaranteed portion is 100% of the project debt, the Federal Financing Bank must be the lender. That is, if the federal government is on the hook for all of the debt, the loan guarantee actually becomes a direct loan.

I've gotten a number of questions on whether this is a good thing. While my answer (that it depends) may seem unsatisfying, thinking about the incentive structure of the direct loans versus the guarantees is quite useful. The same dynamics at play with respect to subsidized credit for nuclear reactors are also involved with other government lending activities -- for example, student loans, a financial activity that has only recently been effectively nationalized.

The direct lending versus guarantee decision involves a tension between direct costs (in which the direct loan approach can be better) and risk vetting (where the decentralized guarantees distributed by other lenders can be better). There is also a trade-off between static efficiency (how you behave when you already know the market and what you need to do) and dynamic efficiency (how you adjust operations to deal with changing market and policy conditions).

For any of these programs, if you know the policy, have trained your staff, and bear all of the default risk anyway, running the lending as a direct loan probably can save money -- both in administrative and markup costs; and potentially in terms of reduced conflicts of interest. The FFB has less incentive to pump up the loan disbursement volume as high as possible relative to a Goldman Sachs, for example.

However, these types of conditions do not apply to all situations. Where policy conditions change; staff needs to be hired, fired, and trained in order to do their job efficiently and well; and there is alignment of interest between the lender and the long-term performance of the loan they are authorizing, direct loans are probably less efficient. While there may be some additional markups on the lending that does go out, the responsiveness of the decentralized organization in terms of finding and vetting opportunities, and monitoring them over time, is likely to more than compensate. The information that the decentralized lenders see, process, and act on can be immensely valuable in making better decisions with better long-term outcomes -- but only if the lenders share a material stake in that positive long-term outcome.

In truth, this issue applies far more widely than whether the federal government should make direct loans instead of guarantees. Franchising is an interesting example of these same tensions entirely within the private sector (credit for this example belongs to Mike Jensen, one of my grad school professors, not to me). The direct financial costs of franchising are much higher than for a parent corporation to simply own the store and hire a manager. But the agency costs -- the losses from the local staff and manager acting on their own behalf rather than that of the firm -- are quite high. Jensen noted that as the number of stores in a particular region grew, the parent corporation at some point would be able to build in sufficient local oversight to overcome the agency costs, and would start to operate company-owned stores rather than franchises. Jensen's papers on this topic are in academic journals and (to my knowledge) are not available for free on the internet. But perusing this book on franchise economics will give you a feel for the issues.

This incentive issue may be part of the logic on the distinction between a 100% guarantee of debt versus lower levels that is made in the Title XVII program: so long as the originator is also at risk, they will execute due diligence on the borrower at the outset, and do a better job monitoring the loan over the course of its life. However, the logic has a few holes even for cases where the feds don't guarantee all of the debt. First, since the DOE chooses the borrower, there is no benefit from outsourcing in terms of deal vetting and selection. Second, while less than 100% federal guarantees may mean the private lender bears risk on the debt issuance (in theory providing an incentive for due diligence), that is not the only possible outcome. Some other party (a foreign government, perhaps) may be picking up the rest of the risk; or the lender may immediately securitize and sell the residual risk onto capital markets. The resulting zero or very small stake in long-term performance of the loan would create a very weak incentive for oversight and management even where the federal guarantees were for less than 100% of debt.

Perhaps the reputational hit to a bank, or internal requirements, or their basic "nature" as bankers would lead them to vet deals anyway? This was an argument a number of banks made themselves in pushing for 100% debt guarantees in 2007. Consider the comments submitted by H. John Gilbertson Jr. (Managing Director) and Alejandro Hernadez (Associate) at Goldman Sachs:

"In addition, DOE’s concern that the 10% non-guaranteed portion is needed to make sure lenders have 'skin in the game' and perform adequate due diligence is inconsistent with the realities of the capital markets. Even when debt instruments are backed by government guarantees and other forms of high-quality credit support, lenders and their counsel do not throw caution to the wind and abandon their diligence efforts. Lenders are by nature 'downside animals' and will perform appropriate diligence notwithstanding the existence of a guarantee, and often their internal policies require them to do so."

I discounted this argument then, and I think my view has been borne out. There is not much evidence that investment banks focused on collecting fees for high deal flow in the area of mortgage-backed securities slowed the production line much to vet the deals or stop them because they were unsound. Where project risks are high, and oversight important, it is not at all clear that maximizing liquidity, or minimizing loan processing or borrowing costs, should trump proper incentive alignment for long-term venture success.

So what makes sense for energy lending? First, a logical incentive structure -- though this issue seems to be mostly ignored by those in DOE and beneficiary industries so focused on making taxpayers a major investor in high risk energy assets. Second, FFB involvement might make sense not just based on percentage of debt guaranteed, but for any deal above a certain size (say $500 million) in which the originator does not retain a minimum percentage of the debt risk over the long term. That approach could avoid paying the private sector high fees for basic issuance of debt instruments over which they are exercising no due diligence anyway; and force greater visibility on the cost of these programs at the federal level. If the FFB plans to sell the debt using private banks, however, care is needed to be sure the banks don't just simply recapture the economic rents at that point.

In addition, the FFB has historically been a mechanism for centralizing financing functions to reduce costs, rather than playing a due diligence role. For such large support to single enterprises as Title XVII and CEDA will entail (far higher than in other government programs), an independent due diligence function -- working on behalf of the Treasury and the taxpayer rather than the policy objectives of the White House or Secretary of Energy -- might make a great deal of sense.