Our op-ed, Tax Expenditure Scrutiny Can End Trillion-Dollar Political Game, was published in Bloomberg Tax today. I wrote the piece jointly with Flurim Aliu and Agustin Redonda at the Council on Economic Policies in Zurich. Flurim and Agustin lead a hugely important effort to build a global database of tax expenditures. It is also a huge undertaking; if you haven't yet had a look at the Global Tax Expenditures Database (GTED), you should. GTED is the only global compilation of tax breaks, and so far they have captured nearly 23,000 provisions culled from all of the official tax expenditure data released by national governments since 1990.

Go to Tax Expenditure OpEd

Budget battles are an annual ritual in many countries around the world. Views on how to best deploy the revenues differ, made all the more challenging since a sizeable portion of the budget has already been promised via mandatory benefits and multi-year commitments made in prior years. Mix in limited tax revenues (there are limits, even with deficit spending) and it's not surprising that the budget process is often contentious. Politicians and heads of state push for their favorite mix of programs and priorities, using a combination of data, persuasion, and arm twisting. The outcomes are rarely efficient, but the process is at least robust and mostly visible.

Not so with tax expenditures. Special exemptions and reductions in what taxes are due from whom, and when they must be paid by, worm their way into legislation, administrative codes, and sometimes rulings in arcane tax cases or administrative hearings. Language may be purposefully opaque to provide more cover for the beneficiaries and their supporting politicians.

Unlike budgetary spending, the total cost to the government of a specific tax expenditure is rarely known in advance. The actual revenue losses will be driven by when, and how extensively, private parties engage in the subsidized activity; and by the macro environment in which they do so. Where governments do estimate revenue losses from the tax expenditures (thankfully, in the US both the Treasury and the Joint Committee on Taxation do so), the estimates not based on budget outflows, but instead on economic modeling that incorporates the eligibility rules, economic conditions, and data from past tax returns. The resultant estimates are indicative of the policy costs, but not nearly as precise as with budgetary outlays. And while the general beneficiaries of the policies can sometimes be guessed, the degree and scale to which specific sectors, firms, factories, or individuals is largely hidden.

The total burden of these special tax benefits is huge. GTED data indicates that tax expenditures in the US and Canada are about 6% of GDP, 8% in the UK, 10% in Ireland, and more than 14% in the Netherlands. The global average is about 4% of GDP, though for many countries there is no data at all. This is not "free" money. Indeed, while nobody likes to pay taxes, it is those tax revenues that fund the governments to establish and operate the many, many activities on which millions of their citizens rely. And when tax breaks are granted to one group in society, the tax burden on those who remain often needs to rise.

As we note in the op-ed:

Similar to direct spending programs, tax expenditures are used to pursue a variety of policy goals including regional development, attracting foreign direct investment, greening the economy, or mitigating inequality and poverty. And like those spending programs, tax expenditure provisions can be politically influenced or poorly structured such that they end up supporting non-target groups or generating windfall gains to the wealthy. The big difference across these two areas is in terms of transparency, and that needs to change.

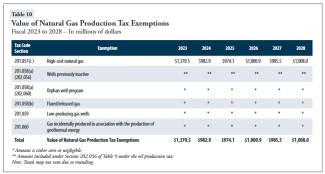

Indeed, there's no way to gauge whether a tax break is achieving its stated policy goal efficiently (or at all) based on the current data. Work by the GTED team has found that more than half of the countries tracked (116 of 218) have released no official tax expenditure report in the past 30 years. Even among reporting countries, nearly a third of the entries have no associated data on revenue foregone through the provision, necessary to get even a rough scale of the magnitude of support. The policy objective the tax break is aiming to achieve is similarly missing in far too may situations. And data at the state and provincial levels is even more sparse, despite indications that these governmental units also provide large tax subsidies to favored sectors. Earth Track recently found, for example, that reporting gaps in Texas resulted in the largest tax break flowing to the natural gas sector in the state ($1 billion in 2022) not showing up in the official tax expenditure reports.

Tax expenditures can be an effective way to achieve useful policy goals, but only if they are subject to the same levels of disclosure and analytical scrutiny as budgetary spending. Absent this, the tax breaks are more likely to flow based on political power than policy purpose, resulting in inefficient use of resources and incentives that often work against social goals being pursued elsewhere in the government.

But it is because of this long involvement that I can see the many ways in which the current work moves the ball on subsidy transparency and reform. Here are some of them:

But it is because of this long involvement that I can see the many ways in which the current work moves the ball on subsidy transparency and reform. Here are some of them: